Performance Works: Documenting Feminist Performance Art

Research and Publication Project by Anja Foerschner

Project Description

|

The documentation of ephemeral art practices is an important, yet highly discussed topic in art historical research. It often provides the only means by which happenings, dance, temporary land art, or performance art, which is the topic of this project, can be examined. However, it seems that the preparation and documentation of ephemeral work, the scripting of events and actions and the curation and archiving of the material are dismissed as having secondary relevance to the “final product”, which is the physical enactment of an ephemeral art piece. Some scholars and artists themselves consider documentation of performance art as unnecessary or even impossible. Peggy Phelan, for example, argued in Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (1993) that “[p]erformance’s only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representation of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance.”[1] Similarly, artist Marta Jovanović stated in an interview: “I believe that performance only makes sense when it is still ‘alive’, when you are in the room and it is happening.”[2] Amelia Jones has argued for the contrary: “[…] not having been there, I approach body artworks through their photographic, textual, oral, video, and/or film traces. I would like to argue, however, that the problems raised by my absence […] are largely logistical rather than ethical or hermeneutic.”[3] She states that it is only in retrospect, when drawing from a performance’s documentation, that performances become meaningful as it is only then that patterns of history can be identified, i.e. a work be interpreted in its respective context. In our highly visual culture, it is not a surprise that a visual remnant of ephemeral art is what we are drawn mostly to. Thus, preparatory material and documentation in other media such as handwritten notes, typed paragraphs, copies, collages, or emails, posts, or snippets of online research in the present, have so far taken a back seat in the researching and exhibition process. Scholarly investigation of these issues is almost completely absent from the discourse. This is the gap in scholarship of performance art that this research project intends to fill. It aims not only to look at the various kinds of documentation, but also at the practices of editing, curating, archiving, and collecting these forms of physical traces of ephemeral art. Furthermore, the project will narrow the thematic focus and highlight especially feminist performance art as these practices broke with the art historical cannon and every-day social interactions in the 1960s and 70s (and continue to do so to the present day). By their inherently political nature, they invite a critical distinction from the larger field of performance art and thus deserve closer consideration. Using examples such as Carolee Schneemann, Barbara T. Smith, Marta Jovanovic, or Kate Durbin, among others, the project uncovers the detailed documentation and meticulous preparation of ephemeral works by feminist artists and foregrounds the curating and archiving practices by the artists themselves. Finally, it will examine the challenges these issues present for institutions, conservators, and scholars with regard to collecting and preserving ephemeral art and their physical traces. Core Areas: |

1, Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, London: Routledge 1993, p. 146.

Image Captions

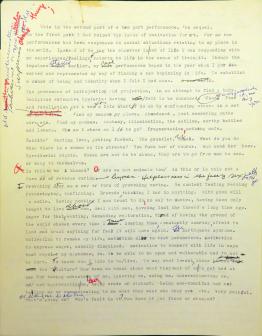

1.Barbara T. Smith, typed and annotated script page, 1977, Los Angeles, Getty Research Institute (2014.M.14), Box 169, folder 1, image courtesy of the artist

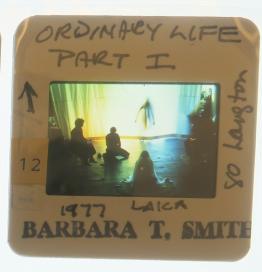

2. n. a., negative of performance photograph of "Ordinary Life" pt. 1, 1977, Los Angeles, Getty Research Institute (2014.M.14), Box 124, folder 13,image courtesy of the artist

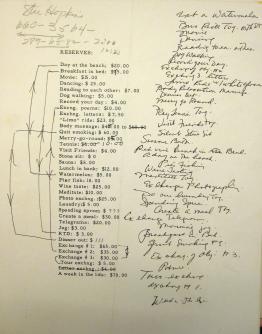

4.Barbara T. Smith, typed and annotated auction list for "A Week in the Life" of, 1975, Los Angeles, Getty Research Institute (2014.M.14), Box 167, folder 16, image courtesy of the artist

5.Kate Durbin, "Hello Selfie Miami," 2015, image courtesy of the artist